She’d never admit it, but Stan’s sister didn’t have near enough money or strength left to keep up that house by herself. There were small things: doors that stuck, a water heater that left red-brown puddles on the basement floor, a split flue tile in the chimney. The foundation, cracked at the corners and still settling, was probably the worst of it. And then there was the roof. She’d had it patched in places, but rain and melting snow still leaked through the asphalt, spreading dark stains on the undersides of the eaves. The last big storm, Sandy had hauled buckets of rainwater through the living room and down the stairs, then dumped them out in the basement drain, where the neighbors wouldn’t see.

All that, and she still wouldn’t hear of letting it go. Never mind that the rest of the neighborhood thought their family was trash, or that Stan was the only pair of hands left to help her. Never mind that on an afternoon like this, the first and probably the last mild Saturday of a long, sweltering June, when he should’ve been in his backyard in a lawn chair with a beer in his hand—or better yet, making love to his wife with the windows open—it was Stan, and not Sandy’s ex-husband or her grown boys, who was out back, down on his hands and knees, scrubbing and sanding the deck.

It was hours scouring the boards before the job was done. When the planks were finally clean and smooth, Stan fetched a broom from the kitchen. He was sweeping away the sawdust when he heard something metal, a ring, ticking against the sliding door. Sandy scowled at him through the glass.

He couldn’t get over how old she was looking these days, how much like their mother. There were crows feet at the corners of her eyes and flat, brown spots were edging out the little freckles that ran along her arms and shoulders. To save money, she’d taken to setting her hair with a kit from the supermarket. Her perm was thin and porous; it radiated from her scalp like a halo of dishwater foam.

Stan turned away, but the next second she was out there with him, breathing down his neck.

“Jesus, Stan, were you just going to sweep it all into the yard?”

She took the broom, handed him a dustpan, and started to move around the deck, gathering the powder into neat little piles. It had been like this since they were kids, Sandy telling him what to do and then how to do it.

There were a couple of wrought iron chairs in the yard, and he thought about how much he’d like to hurl one at the house, put it right through the glass door. But that would cost him too much. Sandy had his job, his house, his whole life in her back pocket. He bent down and held the scoop while she whisked the last of the mess into the pan.

“I have to run some errands. Can you set out some beef to defrost?”

“Sure,” he said without inflection and went into the house.

At the bottom of the stairs, he snatched at a dangling cord until a bare lightbulb glared down on the deep freezer. He walked over and lifted the lid. The inside still had a wispy coat of frost, but it breathed out a raw stink. He didn’t hear the motor buzzing, and when he put his hands inside, he found thawing meat leaking juice all over the bags of vegetables and the softening dinner rolls.

He went to the stairs and called up for Sandy, but she didn’t answer.

“Sandy, goddammit, it’s the freezer!”

Nothing.

He went back to the freezer and dragged it far enough away from the wall that he could squeeze in behind. It was plugged in, and he couldn’t see anything wrong with the cord, so he tried the other outlet. The icebox shuddered once and then started humming.

He got out from behind it and assessed the damage. Everything he thought could be salvaged, fruit mostly, he took upstairs, washed in the sink, and then packed into the refrigerator. He stuffed the meat into a couple of doubled-up Hefty bags, sealed up the freezer as best he could, and pushed it over to the stairs. It wasn’t as heavy as he thought, but it was awkward, and the sound of the blood and water sloshing around inside made him queasy. He dragged it up the stairs and out of the house. In the yard, he turned the thing over sideways and sprayed it out with the hose.

By the time he was done, the sky had turned shades of purple. His back throbbed in time with the crickets. He went inside and settled his weight onto the couch in the living room. Sandy’s husband had left seven years ago, but the room was the same, as if she was just looking after it until he came back. The walls were painted forest green and hung with paintings of outdoor scenes: wolves and winter landscapes, a flush of mallards startled into flight. Richard had taken his six-pound bucketmouth from over the fireplace, but the bare hooks were still anchored to the studs.

During the divorce, Sandy had been so stubborn about the house, so unmovable, that Stan couldn’t help admiring her a little. The sensible thing would have been to let Richard have his way and sell the place, then stick it to him in the settlement and move back to the valley. She could have had a few easy years that way, living off the alimony.

But leaving that house on the hill would mean that she couldn’t walk around with her nose in the air anymore. She would have to go back to being a Hubbard, a low-town cricker. So she chained herself to that big empty house and let Richard and his lawyers walk away with anything else worth taking.

Stan heard noises from another room and when he went to investigate, he found Sandy in the kitchen. Her purse was on the floor, and she was standing in front of the refrigerator with the door open.

“What happened here?”

“Freezer went out. You’ve got a bad outlet down there.”

“Damn it.” She opened the freezer door and shifted things around. “Where’s the rest of it? The steaks, at least.”

Stan shrugged. “It must have been out since the other day.”

“Damn it,” she said again and closed everything up. With her head cocked and one hand on her hip, she looked at him like he was a dog that had shit on her carpet. “What about the deck, you didn’t get the sealant on?”

“No, Sandy, I was a little busy lugging your freezer around.”

She sighed and shook her head. “Well, it couldn’t take more than an hour, could it? If we get started now we can put on a first coat at least.”

Stan went to the sink and started washing up. “It’ll keep. Besides, I told Mel I’d be home for dinner.”

“Call her, then,” Sandy said, brightening. “We’ll make something here. It’ll be a family dinner. Oh, and she can stop by the store. I mean, it doesn’t look like there’s much left here.” This too was somehow his fault. “I’ll make her a list,” Sandy said and tore a sheet off the pad stuck to the refrigerator.

Stan’s jaw tightened. “You ever think that maybe I don’t want to spend every night over here, that maybe it’s not my purpose in life to be your step and fetch it?”

“Don’t be nasty.”

He dried his hands, and when he crossed the hall to the bathroom, she followed him. “I’m going home,” he said, searching through the cabinet until he found the Tylenol. He tossed a couple in his mouth and then scooped in water from the faucet.

Home. That was a joke. For two years, Stan had been living in his dead mother’s house. Before that he’d been in Kansas City, broke and out of work. Sandy had found him a job in Hopsville and given him Mom’s house to live in. He’d hated the idea, but it was a rope dropped down a dark hole, a way out of the mess he’d made of his life, and he’d grabbed for it. She’d done right by him at the time, and he was grateful. But that was two years ago, and this was now.

“All right,” Sandy said. “We’ll just have to get an early start tomorrow.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, we can’t leave the deck like that—what if it rains? And you need to mow the yard. You know you’ve been putting that off for two weeks now.”

“Mow it yourself.”

Sandy leaned across the narrow doorway. It was clear she wasn’t going anywhere, so Stan shoved past her into the hall.

“And while you’re at it,” he said, “why don’t you drag that freezer back to the basement? You could fix the outlet while you’re down there.” He opened the front door and left it open. “I’ve got news for you, Sis, I’m not your handyman, and my wife isn’t your goddamn maid.”

At home, Stan parked the hatchback in the garage, set his toolbox back on the shelf, and went inside. Melina stood over the stove, stirring ground beef into a sizzling mash of olives, raisins, and boiled eggs. He took a slow breath through his nose and held it, savoring the scent of simmering wine until cayenne tickled his lungs.

His mother’s house had never smelled this good. A childhood of instant mashed potatoes and dry, grey-white pork chops hadn’t prepared him for Melina’s cooking: for slow-grilled short ribs bathed in chimichurri sauce, for cumin-spiced meat pies filled with red peppers, for sweetbread and chitlins.

Melina had thickened in the handful of years since the wedding, but Stan didn’t mind. He took a moment to admire the way her sundress clung to the shape of her hips, then put his arm around her waist and nuzzled her.

“So, how is Mr. Foster doing? Did he try to dance with you again?”

“The poor man,” she said and turned off the burner. “Sometimes he thinks I’m his wife. If no one looked after him, he would spend the whole day in dirty pajamas and never put his teeth in.” Stan got a beer and sat down at the faded Formica table. Melina got plates from the cabinet and started setting their places. “How are things at Sandy’s?”

He shook his head and got up from the table. “I don’t want to talk about it.”

“Was there a fight?”

“It’s nothing. I need to take a shower.”

After dinner, Stan settled into the recliner, the one his mother had slept in most nights near the end, and graded the last of the summer-school papers. Melina opened the doors to the mahogany cabinet that held the old console television and the record player. She flipped through the channels but then settled on the usual sitcoms.

When he couldn’t bear to read another confused essay about the Declaration of Emancipation or the Compromise of 1977, Stan joined her on the couch. The Dirty Dozen was on cable, and he tried to get her to watch it through to the end. She fell asleep somewhere in the middle, and by the time the assault on the chateau was done and most of the men killed by snipers, Stan was thinking about his sister again.

He could never figure what Sandy saw in that house. It had been out of place to begin with, and even though the neighbors wouldn’t say it to her face, they still held a grudge. Widow Best had lived quietly on that spot for seventy years. But then some bad wiring had shot off a spray of sparks in the den, and flames scorched her grand Victorian to the foundation stones.

That was tragedy enough, but Richard and Sandy had done the unthinkable. Without consulting anyone, they had swept in, bought the lot, and raised a modern split-level in the midst of the all those gingerbread manses. As far as the rest of the neighborhood was concerned, the place should have never been built. It was a scandal from base to boards.

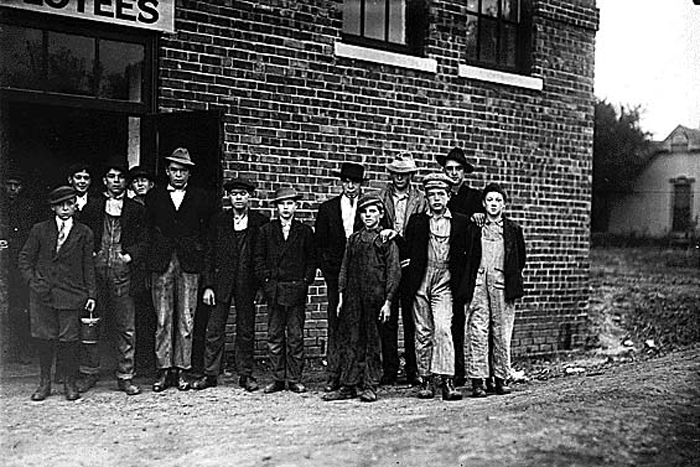

Besides, everyone knew that Richard Gooch had married down. Most families on the hill were the descendants of Hopsville’s founders, gentleman farmers who’d left Kentucky for Missouri. The rest were heirs to the bankers and factory bosses who, not long after, had bought the town outright. Stan’s sister was the only exception. Her people had been the cast-offs from neighboring counties—penniless latecomers who had set up shanties at the edge of Hog Creek, toiled in the shoe factory, and caused trouble in town. Later generations hadn’t done much to improve the family’s reputation.

Their father, Frank Hubbard, had been one of the worst. A hard drinker who liked to fight, he’d spent more than a few nights in jail. At home he was moody and free with his fists. As a boy, Stan had put his body in the way of it, tried to keep the old man off his mother and Sandy. When Stan showed up to school with bruises or a black eye, the whole town knew who was responsible. Sandy could put on airs, but she was Frank Hubbard’s daughter, and the Hubbards would always be creek people.

Melina stirred, and they both got ready for bed. She changed into her nightgown and stood in front of the bathroom mirror. Watching her like that, as she brushed her teeth and spat into the sink, Stan could almost forget about Sandy and the house, about the suffocating feeling he got whenever he pictured the rest of his life pinned to this speck on the map, his future tangled up in its tiny history.

He thought about the way Melina kissed him, like there was still something in him that she needed to go on living. He thought about how, after they made love, she would sometimes swing one leg across him and wiggle her ass with happiness. Just now, waiting for her to come to bed, he could breathe again.

The next day, a sound like an angry dog jolted Stan awake. Nine-thirty in the morning and Bill Tender was roaring down the street on that ridiculous crotch rocket.

Stan got dressed, put on some coffee, and then sat down at the kitchen table with the Hopsville Dispatch. There was an ad in the classifieds for an apartment in the low part of town: clean, two bedroom, not far from the Food Barn. If Sandy was smart, she’d put the house on the market today and get herself a little place like that.

Melina came back from Sunday mass, and they ate lunch together. Afterward, she traded the simple dress and rosary for a bikini and a trashy novel and lay sunning herself in the backyard. Stan had a little fun menacing her with the hose then went around front to wash the car.

He was waiting for the wax to haze when the phone started to ring. He didn’t move to answer it.

“If it’s Sandy, I’m not here.”

Through the kitchen window, he watched Melina pick up the receiver and turn away. He was moving the shammy in wide loops across the hood when the screen door slammed. Melina stood on the front porch with no towel or robe to cover her, giving the whole neighborhood a good look.

“What’s with you?”

“It’s Sandy. She was mowing the yard.”

“Yeah?”

“There was an accident.”

Melina went inside, and Stan lifted the phone off the counter. He heard a voice on the line but couldn’t understand what it was saying or why the words were making him dizzy. He had to ask for it all again.

The mower had taken the tips of three toes, the voice told him, on Sandy’s right foot. She had lost some blood, was shaken up, of course, but she was going to be fine. He hung up the phone and put his hands on the counter to stop them shaking. He wasn’t going to feel sorry for her, a grown woman who couldn’t mow her own yard and didn’t want to learn.

A little unsteady, he went over the recliner in the living room. He took the paper from the side table and unfolded it. Melina rushed to the front door and dug in her purse for the car keys. “What are you doing?”

“Nothing.” He tried to read, but he couldn’t put the words together.

“Your sister is in the hospital,” she said, as if there might be some misunderstanding. “We have to leave.”

“I’m not going over there. Think about it, me kneeling at her bedside—‘oh, poor Sandy, please forgive me.’” He pulled out the sports section and unfolded it, rattling the paper to emphasize his point. “It’s just what she wants.”

“It’s not a trick, Stan. She’s in the emergency room.”

“They said she’s stable. That means she’s going to be fine. Look, you don’t know her like I do. Three toes to have the last word, to make sure I know who’s boss? A bargain at twice the price.”

He looked down at the paper, focusing on a photo from ringside: one fighter on his back, the other man lording it over him, daring him to come back for more.

“Sos un forro,” Melina said. She left the house and made a big show of slamming the door behind her.

The rest of the afternoon, Stan sat on the back porch with a cooler of Budweiser and watched the fading sunlight. At first he felt guilty about not going with her, but after the third or fourth beer he was able to forget about it. Across the alley and days ahead of the holiday, the Tender kids were launching screamers out of coke bottles, two or three at a time. The little rockets whistled over the roof then ran out of breath and blew themselves apart.

Stan had always loved the Fourth of July. When he was a boy, the whole family had gotten up before dawn. His mother served flapjacks with maple syrup for the kids, pork chops and scrambled eggs for their father and Uncle Jimmy. The men, still drunk from the night before, drank mugs of black coffee then headed into the woods with fishing rods and tackle.

As soon as the sun was up, Stan would burst outside with the paper bag from the fireworks stand. He set up Folger’s cans on the fence posts, dropped in sizzling cherry bombs, then dashed to cover before the blast launched them into a neighbor’s lot. Mom sat on the trailer steps with her cache of Winstons. She stared out at the road and lit each new cigarette with the glowing stub of the last one. Sandy and Stan lit Black Cats and strings of Ladyfingers, and when Mom went inside to fix lunch, they stole off to the toolshed, took down a hammer, and burst the unexploded ones against the concrete.

In the evening, Dad would shimmy out of the pickup truck, a bag of ice over each shoulder, and Jimmy, still whistling “Yankee Doodle”, would set a pine barrel on some patch of level ground. Mom would go inside to fetch the milk and sugar while Dad smashed up the ice to mix with rock salt. Jimmy would set Sandy on top of the churn, and Stan would work the crank, mashing everything together with walnuts and strawberries from the garden. Before Melina came along, those had probably been the happiest days of his life.

Stan was dozing in the recliner when he heard the garage door open. The streetlight on the corner was buzzing, and for a solid minute he couldn’t tell if it was night or early morning. He brushed sandwich crumbs from his shirtfront and took the empty plate into the kitchen.

Melina was sitting alone at the table sulking over a platter of cold cuts; she had a little knife in her hand and was using it to cut thin slices from a wedge of Chubut. Stan put the plate in the sink. When he pulled out a chair, it made a scraping noise against the tile.

“So,” he said, half-sitting, half-falling into the chair, “how is she?”

“You’re drunk.”

It was hot in there, and he could feel his hair, thick and damp, against his forehead. He raised his hand to untangle it but then thought better of it; that would only make him look guilty.

“A few beers,” he said and scratched the back of his neck. Something behind him started twittering and then launched into a full-throated shriek. He turned around, expecting to see—he didn’t know what, maybe a starling drowning in the sink.

Melina took the kettle off the stove. She poured herself a cup of tea and stood at the counter. He could see now that she had been crying.

“What are the doctors saying?”

“Another surgery tomorrow,” she said. “A specialist from St. Louis. They say he’s a friend of Richard’s.”

Sandy would like that. It meant that she could still play the doctor’s wife.

“The toes. They’ll be able to save them?”

“Yes, they think so. But walking will be hard for her. It will take time.”

“La invalido, huh?” He tried to sound good-natured, as if the whole incident had been a practical joke. He got up from the table and touched her arm.

“Look. Don’t let her fool you. Sandy’s tough as leather. Oh, she’ll gimp it up for a few weeks all right, see what she can get out of it, but believe me, she’ll be up and around in no time.” Melina took a sip of her tea then set the mug on the counter and walked out of the kitchen. Stan followed her into the bedroom.

“What? I’m sorry, okay, I shouldn’t have made you go by yourself.”

“You’re her brother, you’re supposed to help her.”

“Help her? Jesus. What have I been doing for two years now? Cleaning out her gutters, hauling ass up a ladder—”

“Stop this,” she said. “You have to stop.” She took a deep breath and when she looked at him, her eyes, her face, every part of her was still.

The next day, Melina called off work, and they went up to Sandy’s place. When they reached the old lane that formed the Northern boundary of the town square, the hum of concrete gave way to the regular thumping of red bricks. It was almost Independence Day, and ranks of cellophane pinwheels had sprouted in the lawn behind City Hall. They twirled above the sod in anxious, shimmering circles.

“She’s selling that house,” Stan said. “I’m not spending the next twenty years holding up the walls.”

At the bottom of the hill, he glanced at the marquee for Kaleidescope Video; in black plastic letters, the owner had spelled out: save a home. shoot a banker. As they climbed the hill, the houses of Hopsville’s best families paraded by, the railings of their wrap-around porches draped with star-spangled fans.

“You sound like her, you know.”

“What do you mean?”

“A martyr.” She was smiling slightly, but mostly she looked tired. “Saint Stanley.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“We chose to live here, to be a family.”

“No,” he said, shaking his head, “we didn’t have a choice.”

He’d put twenty years between himself and Hopsville, all but six of them in Kansas City. An honest-to-God city, with bronze statues and fountains. A Major League team. Shopping malls and freeways.

But Stan had ruined everything. He’d been teaching at Westport, the shittiest urban school in the district. It was a place with metal detectors but no air conditioning, where the students regularly called him a “motherfucker” and a “faggot.” The bastards had torn the radio out of his car and taken a razor blade to the office chair he’d brought from home. Once, one of the older boys had tried to push him down a stairwell. He’d managed to tolerate it somehow, holding on to his rage just long enough to get to the teachers’ lounge or the parking lot.

But on that day, one of the little thugs, fresh from an out-of-school suspension, strutted into the wrong class. He took a seat in the back row and just shot the shit with his friends like Stan was nothing to worry about.

Wouldn’t leave, wouldn’t shut up.

Stan heard the words—“Go fuck yourself”—and then a sharp sound, like a book slapping the floor. Stan’s hand started throbbing and three of his fingers went numb. It wasn’t until the blood was flowing that he realized what he’d done.

Even with the teacher shortage, no school in the city would hire him after that.

He said it again, this time just to himself. We didn’t have a choice.

Out back, there was no sign of the freezer, but the old mower was there, overturned in a patch of rough grass. He tilted it right-side up and unscrewed the gas cap. Gasoline sloshed inside, shimmering where the sun hit it. He replaced the cap and pumped the button a few times to push fuel into the line.

He cut the perimeter first, carving a pattern of straight, clean lines through the yard. The old mower didn’t have a catch, and it spat clippings that stuck to the sweat of his ankles. Halfway through, he peeled off his soaked T-shirt and threw it over the deck railing. It hung there like a soiled flag of surrender.

When the job was done, he shut off the mower and wheeled it into the garage. In the laundry room, he rummaged through a hamper until he found a bath towel. He rubbed it quickly over his wet scalp then snapped through a rolling rack of Richard’s old island shirts. He picked one and tugged it off the hanger. It was tight in the shoulders and patterned with hula girls, but he buttoned it up anyway.

The carpet in the living room was tracked with fresh vacuum marks, but a pattern of splotches, the color of an ugly bruise, marked a path from the sliding door to the low coffee table. He imagined Sandy crawling into the house, groping for the cordless, and then slumping over the arm of the couch to wait on the ambulance driver. Picturing her hurt like that and all alone, it made him want to be angry at somebody. He would have been, too, if he could just settle on who it should be.

As he stepped into the hall, Melina came down the stairs, an overnight bag slung over her shoulder. She’d been good with him that morning, better than he deserved.

“That shirt,” she said, cupping a hand over her smile. “Where did you find it?”

“In the garage.” He grinned and stuffed the tails into his jeans. “From the museum of Dick.”

“We should go. The doctors will be putting her down soon.”

“Under,” he said. “They’ll be putting her under.”

When they got to the driveway, Stan started up the car. But then he just sat there, staring at the house. It had made him so angry, thinking about everything, that he hadn’t put the car in gear.

“Stan?”

“She had no business keeping this place.”

“Stan,” Melina said again and rested her hand on his leg.

“No business at all.”

At the hospital, they waited at the front desk behind a delivery man. The back of his neck was the color of a beefsteak tomato, and he smelled faintly of fertilizer. The nurse behind the counter signed and returned his clipboard. When Stan and Melina stepped up to the line of yellow tape, she seemed to still be admiring the white-washed basket filled with sunflowers and blue daisies.

“We’re here to see Sandy Hubbard.”

“Gooch,” Melina corrected. “Sandy Gooch. They moved her this morning.” The nurse reached for the basket.

“These just came for her.” The desk phone rang and she answered it. Propping the receiver to her ear with one shoulder, she flipped through the pages of a binder. “407,” she said, not looking up. “And would you mind taking these? You’re going already.”

“407,” Stan repeated. He lifted the basket off the counter and followed Melina to the elevator. When they got to the room, Sandy was lying in bed with her eyes closed and her mouth open. Stan set the basket on the ledge under the television, and Melina approached the bed.

“Sandy, it’s Melina and Stan. Are you awake?” Sandy blinked and rolled her head on the pillow. She looked in Stan’s direction, as if she didn’t quite recognize him.

“Look who decided to show his face.”

Melina gestured towards the basket. “Someone sent you flowers, Sandy.”

“Oh,” she murmured, propping herself on one elbow. “Who are they from?”

Stan slipped the card from under the bow.

“A lot of people, I guess.” He read over four or five of the names before he realized what they had in common. “The school board.”

“That’s nice. Some people know how to act.” She smiled and eased back against the pillow. The same look as at Mom’s funeral, her and Melina half-concealed behind a wreath of red and white carnations. They’d made the deal right then, he was sure of it. Sandy would give up her share of Mom’s house on Flood Street. She would throw her weight around with the superintendent, open up a spot for Stan at the high school. But it would be up to Melina to talk him into it, to convince him to give up on Kansas City. To fetch him home for good.

“Does it hurt?” he asked.

“Like the devil, but what do you care?”

“Maybe we should go now,” Melina said, “and let you rest.”

The bedsheets covered Sandy’s feet, bulging over the bandaged one. It was strange to imagine the carefully painted tips of her toes underneath, now purple or black, the cut ones at least. He pictured them sewn back to the stumps with a crooked ring of stitches, like she was the bride of Frankenstein.

“I almost forgot,” Sandy said, “I told the Campbells they could use the ice cream maker.”

“The one Uncle Jimmy used to bring around?” Stan pulled aside the flimsy curtain and looked down on the parking lot. “What do they want with it?”

“It’s for the little ones. Don’t you remember,” Sandy said, “it was every Fourth when we were kids.”

“That thing’s an antique,” Stan said. “Probably rusted out.”

“Look at Mom’s place for me, see if it’s there.”

“Our place. That’s what you meant to say.” He turned away from the window, ready to start something, but Melina’s look asked him to let it go. “I haven’t seen it,” he said.

“You haven’t looked.” Sandy gazed down at her hands and smoothed wrinkles out of the hospital blanket. “Just leave it in the garage the next time you’re over to my house. Brenda will be by for it.”

“Brenda Ross? The one who started everyone calling you ‘shit cricker’ in the cafeteria?”

“It’s Campbell. It’s been Campbell for twenty-five years now, what’s wrong with you?”

Stan fidgeted with the flowers, plucking pastel spears off the daisies. They don’t have enough of their own, he was about to say, they have to help themselves to what’s ours? But just then one of the nurses breezed in, a flat-chested girl in a blue smock.

“How are you feeling, Mrs. Gooch?” She moved about the room with a casual efficiency, checking on the monitors and the IV. “We need to get her ready for surgery now. You can see her after.”

“We brought some of your things,” Melina said, and set the bag on the floor. “I’m going to leave them right here.”

She raised up, ready to leave, but Sandy caught her by the wrist.

“Don’t let him forget. You know how to talk to him.”

By the time it was all over, the sun was nearly down. On the drive home, Stan imitated Sandy’s voice, the husky jangle of it, like shaking a sack of broken glass.

“You know how to talk to him.” Melina hid her eyes behind a pair of sunglasses and leaned back against the headrest. He waited for her to show some sign of support or say anything, really. But she just sat there.

“The two of you,” he said. “You’re in it together.”

“Fine.” She made gestures in the air, as if she were casting a spell. “We made a witches’ bargain. Cursed you with a job and a place to live, washed your clothes and cooked your meals.”

“I think we both know Sandy never made a meal worth eating.” He forced a little laugh, but Melina ignored him. “Look, you’ve seen how it is. In St. Louis or Kansas City, nobody cares if your uncle couldn’t pay his debts or your granddad got hammered in the middle of the day. But around here? It’s sins of the father for seven generations.”

“We have sins of our own.”

“Oh, give it a rest, will you?” He shifted in his seat and then put his hand over hers. “Sure, we did some sneaking around at the start, but the way he treated you, that pig, he’d given up any right to call you his wife.”

“Not that,” she said, drawing her hand away. “What you did to that boy, it was terrible.”

Stan’s body gave a jerk, like taking a shot of bourbon. They’d talked about it before—what to do, what he would say if lawyers got involved, reasons, even, for how it happened, what had gotten into him. But this was different. She was saying he was a bad man, that he ought to be ashamed of himself.

Something started to rise up in him. It made him feel small and fearful and it was going to swallow him up if he didn’t do something about it. Panicked, he reached out for his anger.

“It must be nice to have a clear conscience,” he said. He pulled up to a stop sign, took one hand off the wheel, and crossed himself. “How about I do ten Hail Mary’s, and you can bathe me in the blood of the lamb or whatever and we’ll call it a day.”

“Que disparate.” She looked away, shaking her head. “Pull in there,” she said and pointed to the lot in front of the Always Save. “We need some things from the store.” He pulled up to the curb, but before he could cut the engine, she was stepping out of the car. “I’ll see you at home.”

He leaned out the window and called after her. “So, what, you’re walking back?” She showed him the back of her hand and then the automatic doors closed behind her and she was gone.

Once he was home, he tried to forget about the argument. He knew that if he thought about it too much his chest would start to burn, and juices from his stomach, tepid and sour, would rise to clog his throat. He started in on a documentary about the Civil War, then thought about going down to the basement. He’d seen the ice cream maker down there a few days ago behind a box of old photographs.

He went out to the driveway, lifted the car’s back door, and folded down the seats. If Sandy really wanted that old junk, she could have it. He’d drive over to her place, let himself into the garage, and leave a heap of it next to the mower, right in the spot where Richard used to park the Lincoln. He loaded Mom’s tv first, wedging it in with boxes from the basement. Three trips and the car was packed full. He settled the ice cream maker into the passenger side and got in.

He didn’t want to cross paths with Melina, so he took the back way to the hill. He skirted the edge of the railyard, crossed the tracks, then passed under the factory’s shadow. As he approached the one-lane bridge over Hog Creek, a shape moved at the edge of his headlights. He laid off the gas and a woman—no, a girl—came into focus. Headphones covering her ears, she was ambling beside the guardrail, deaf to the world.

Stan blew the horn as he passed, just to scare some sense into her. When he checked the rearview, she’d moved to the middle of the bridge. She was standing in a flickering band of streetlight, shouting after him. Her fists were out, and she was punctuating the air with her middle fingers.

Stan’s teeth ground together, and sweat stung his forehead like an insect he wanted to swat. He hit the brakes hard enough to leave a mark on the road but then just gripped the wheel and let the engine idle. He’d left the girl a few yards back, but she was closing the distance.

She should have been frightened, alone in the middle of the night with an angry man. She should have turned away and run home. He’d teach her a lesson, goddammit, show her what she should’ve learned already: that a man was a thing to be scared of.

He unlatched his seatbelt and stepped out onto the bridge. He was trembling, thrilled and frightened at the same time. Something was going to happen now, he was sure. He didn’t know if he’d be able to stop it or if he wanted to.

“Hey,” the girl shouted, “asshole!”

The tendons in his neck went taut.

“What the hell was that? You think—” She stopped in mid-sentence, then went bashful. “Oh God,” she said, stuffing her hands in the pockets of her jacket. “Mr. Hubbard. Jesus, I didn’t know it was you.”

Stan just stood there blinking at her. There was a tinny throb coming out of the little speakers around her neck, a sound like a car that wouldn’t start. The ground beneath him wobbled, and he had to put his hand on the back window to steady himself.

“Mr. Hubbard?”

Why had he gotten out of the car? Why had he stopped in the first place? His hand slid along the hatch until he was sitting on the bumper.

“Are you okay?” The girl crouched next to him, her tangled hair glowing in the brakelights. Stan made a noise like a hiccup or a muffled sob. Maybe Melina was right; maybe he wasn’t a good man after all. “Mr. Hubbard?” Stan nodded. He drew one arm across his eyes, sniffed hard, and tried to shake it off.

“You’re Jay Lobe’s girl, aren’t you?”

“That’s right.”

The teacher’s lounge had filled him in on the Lobe girl long before she showed up in his homeroom. A year older and a head shorter than the other girls in her grade, she’d made her reputation early. She’d tackled Betsy Campbell in the lunch room and yanked a fistful of blond from the girl’s scalp before the monitors could break it up.

“What are you doing out here?” he asked, mostly to buy some time. The world had begun to right itself, but his breath was still coming shallow and short.

“My dad’s pissed,” she said. “It’s nothing, just a bad night.”

Stan had grown up with Jay Lobe. A mean, snub-nosed bully who’d only gotten worse with age. No question, any daughter of Jay’s had already seen her share of bad nights. Stan didn’t feel like yelling at this girl anymore, or scaring her, or whatever it was he thought he was doing out there. There was no sense to it.

“You moving or something?”

“What?” he said, then remembered the pile of junk in the car. “No.”

The Lobe girl looked over her shoulder to the far bank of the creek, as if there might be someone back there who could tell her how long she had to stand here or what she was supposed to do.

“You sure you’re all right?”

Stan nodded. “I was just working today,” he said, “in the yard. The heat.” He reached out one hand and pushed against the bumper with the other. “Help me up, okay?” He fumbled in his pockets for his keys then realized they were still in the ignition.

“Look,” he said, “it’s dark. Why don’t I give you a lift? It doesn’t have to be home.”

She looked him over, his red face and his rough hands, then shook her head. “Thanks anyway,” she said, pulling her headphones over her ears again. “I gotta go.” Stan watched her cross the bridge, her pace faster now, until she was out of the reach of his headlights.

He walked once around the car, just to make sure he had his legs under him, then climbed inside. On his way to Sandy’s house, he started to think about the Lobe girl’s father and his own. But he didn’t let it go too far. For years, he’d done his best not to think about the old man. That invited comparison, and he didn’t like what they had in common.

Stan pulled into the driveway. He lifted the garage door and took the ice cream maker inside. He set the barrel and the crank on the bare floor, next to the mower. Back at the car, he opened up the hatch and sized up the load, trying to decide what to take in first: a stoneware jar from the days when the bachelor uncles let the hogs go hungry and fed corn cobs and bails of barley to the still; an army parachute, dyed red for a blanket; a framed picture of a dead boy in a dapper suit, lost when his scarf snarled around a wagon’s spinning axle. It seemed pointless to him now, and low, to leave all that junk for Sandy to come home to.

The hatch made a solid sound when he closed it. He pulled down the garage door, leaving it open a crack for Brenda Campbell, and got back in the car.

There wasn’t any starting over, not really. But maybe the Hubbard men didn’t have to be bastards all the way down the line. He could give Melina a baby. There was probably time enough for that if they wanted it. They could still wring some good years out of this place. Halfway down the hill, he took his foot off the gas and coasted, letting the bulk of those old things bear him back into the valley.