There was once a man in our town who could sleep longer, more deeply, and more beautifully than anyone else. Not a native of this place, Don Albani appeared one morning at the bridge that spans the Esarulo, a little river that bounds our parish at its Western edge. Seen from our ramparts, he seemed less a man than a bare and twisted tree sprung up from the stones of the old viaduct. Three times we spied him at an arch’s crest. In each instance, he paused for a long moment before descending again into the shroud of fog that swaddled the bridge. We might have mistaken him for a trick of the mists had he not manifested at our gate and, making use of the lion-faced knocker, made his presence known in all its solidity.

Once inside, he crossed the piazza and proceeded directly to the office of the municipal clerk. There the stranger declared himself the sole living descendant of the Albani (an illustrious name not spoken in these parts for generations) and therefore due by hereditary right to some land hereabouts. Possessed of documents substantiating both his crest and claim, signor Arturo degli Albani took possession that very day of the chestnut orchards and the lowland cottage that comprised his patrimony.

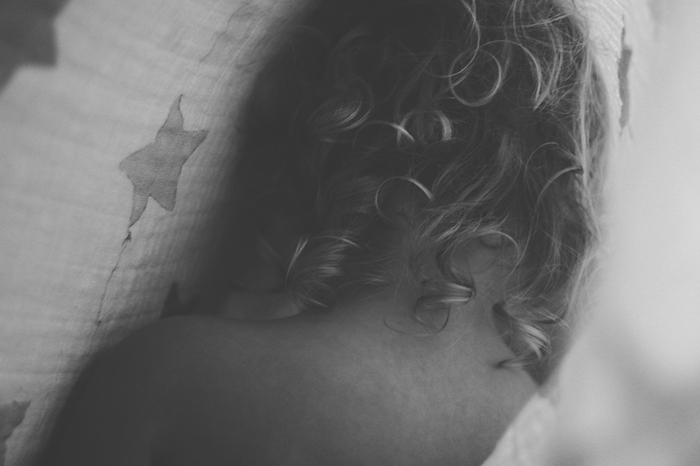

At first, the Don didn’t mix much with us, taking apertivo at the inn maybe one evening out of twenty and then staying only long enough to fortify himself with a few olives, a slice or two of salted tomato, and a glass of red vermouth. His head was crowned with soft ivory curls, and he smelled of rosewater and fresh wood shavings. He was rangy, with a long sharp face, but his gauntness suggested more the self-denial of an anchorite than the privation of a beggar. His clothes were rumpled, though finely made, and he often adorned his jacket with a red poppy, only slightly wilted. On those few occasions when he lifted his glass to join us in a toast, one of his sleeves would draw back from the wrist to reveal a lacey cuff.

It was obvious that the Don had once been a person of some distinction, but it was not until the first seekers arrived that we learned of his fame in the courts and great cities of the country. Hollow-eyed men afflicted by the eternal wakefulness of insomnium gathered like shades in the corners of the inn, the rawboned fellows brooding over glasses of warm milk but never renting a bed. Soon others followed: men who snorked and grunted like horses, sleepers seized by fevers who drenched their bedclothes, hysterics who screamed and thrashed through the night—all these and more came to seek the counsel of that venerable gentleman, honoring his name with the epithet “the master of sleep.”

We learned from these supplicants that the good old man had, in his day, been the foremost practitioner of the somnolent arts. He possessed knowledge of every growing thing and could, from raw and unfinished nature, distill oils and tinctures with the power to either dampen an ardent spirit or transmute the base lead of torpor into the lustrous gold of vigilance.

But the maestro’s reputation was not founded on such incidental pursuits. The people had reserved their highest praise for one of his talents in particular: his ability to fall, instantly and at will, into a voluptuous sleep from which he could not be roused until the precise moment of his choosing. Before the art of sleep fell out of fashion at court, his performances had been staged in a canopied bed in the most illustrious hall of the palace and always drew a great crowd. He was thought to be very handsome then, and more than a few of the unmarried ladies in the capital (and some of the married ones too) were known to keep tiny portraits of the artist concealed in their dressing tables. A countess, famous for her boldness, was even said to possess a locket containing a golden curl surreptitiously snipped from the sleeper’s tousled head.

Later, when the identity of the old Don was widely known in our region, it became troublesome for him to receive so many visitors in his modest cottage. So, gracious man that he was, he agreed to make himself available for counsel at the inn on the evening of each new moon. Arrangements were made, and a corner table in the common room was set aside for his use.

To preserve the discreet character of his consultations, the Don himself provided an Oriental screen consisting of panels of mulberry paper framed by slats of lacquered cherry. This only heightened our interest in the interviews by lending them an air of mystery. Further, the lamp set between physician and patient projected their outlines onto the screen, transforming each encounter into a shadow play.

Despite his good works and the prestige he brought to our town, the maestro’s presence among us was not without controversy. Some whispered that the ingenious old man must be a witch, his great knowledge an infernal boon granted by Lucifer to his staunchest servant. A few said openly that the Don was no different than that gravedigger from Magasa, the one who had come through town with a sack of paupers’ bones, passing them off as true relics of the saints. These men swore, one to the other, that if this proud fellow proved to be a charlatan, he could expect the same treatment as the other: a shorn head, a shirt of pitch and feathers, and a ride through town on a fence post.

But there was one, Baldo the printer’s son, who resented the Don’s celebrity more than all the others. Just as the inked impression is backwards to the block that makes it, so Baldo’s nature was in perfect contradiction to that of his gentle and fastidious father. The printer had been a widower and too tender-hearted to beat the boy, and so with no mother and no blows to correct him, the wicked child had gone about doing whatever he pleased: chasing girls with fresh-cut switches, setting dogs’ tails on fire, and forcing his will on the younger boys. Never learning to read himself, the son scorned his father’s trade. When he came of age, he left our town and entered into the service of a condottiero, one of those disreputable princes whose banner can be bought with gold.

It was a few weeks after the Don’s arrival when the prodigal returned from his years of soldiering. He asked after his father, and it was with heavy hearts that we told him of the good man’s fate. The previous winter, the old printer had been shaken with a fierce ague and, after three days, had returned to the One who had formed him from the dust. Upon hearing this news, Baldo displayed no signs of anguish, but instead set to carousing at the inn, drinking all through the days and evenings and telling stories of his exploits to any who would listen. He was still there when, on the appointed night, Don Albani arrived with his screen. A reverential quiet settled over the common room, broken only when Baldo asked who this old man could be and why everyone paid him such deference.

Informed of the Don’s mastery of the art of sleep, Baldo crumpled his swinish face and one of his ears—the tip of which had been mangled in some battle and was now clipped like that of a fighting dog—flushed red and twitched.

“Any man can sleep,” he bellowed; there was no special science to it. Once, he boasted, after a five-day forced march through the marshes, he’d collapsed on the damp ground and slept straight through a cavalry charge. He began to relate more of the story, but no one minded him. The Don was seated with his first client and all eyes turned to watch the shadowy spectacle. In spite of his anger at being upstaged, Baldo waited until the Don had concluded his first interview before crossing the room and rapping on the screen.

“My good sir,” the Don said, stepping from behind his paper shield, “I’m afraid I can’t see you now, as several are already waiting. But if you will write your name and the nature of your malady in the ledger there—”

At the mention of writing, Baldo bristled. “What I need from you—and right here and now—is satisfaction for this itch I have.” He leaned in close and seized the maestro by the forelock. “It’s my nose, you see. Whenever it comes near a liar, or a cheat, or a rascal, it begins to itch and to vex me.” He pressed a fistful of snowy curls to his face. His nose—a ruddy thing overlaid with a skein of broken veins—flared and snuffled like a hog’s. “Just as I reckoned” he said, releasing his grip, “you’ve got the stink of a swindler on you.” Leaning back, Baldo folded his arms across his chest. “You’re no kind of master, you wily old crow, not of any honest craft.” Those present raised up a cry, appalled to see the good old man so abused. But, languidly lifting his arm, the Don bade us to be silent.

“The drunkard’s insult must sometimes be endured,” he said, smoothing his hair back to its natural shape, “for he does not know what he does and may even beg forgiveness when the spell passes.” The Don then brought one hand to his breast and unhooked the blossom fastened there. “Yet the dictates of my order do not allow for me to be indulgent in a circumstance such as this. You have insulted my honor—which, in itself, is of little consequence. But you have committed another, graver offence. You have impugned the eternal verity of the Stygian arts. And that, sir, must be answered.” The poppy fell in a slow spiral, turning three times in the air before landing on the toe of Baldo’s boot. The brute furrowed his brow, then bent to retrieve the flower.

“Ah,” the Don said, “So you accept my challenge. All the worse for you.”

“You? Against me? I’d break you over my knee like a bundle of dried sticks.”

“And so forfeit the trial by slumber by laying hands on your adversary? That’s no strategy, friend.”

“A trial? What are you on about?”

“A contest, one with a storied history among the members of my order. Each of us shall lie flat on our backs and, as soon as we are able, allow sleep to overtake our senses. The first man to wake concedes defeat.”

“I’d just as soon drag you out by your ear and dash your skull against the cobbles.”

“But what would that prove?” posed the Don. “The question is not of your strength, but of my art. If, as you say, I am a fraud, what could you possibly have to fear from such a contest? Weren’t you saying before, if I heard you correctly, that you could sleep even in the midst of a battle?”

Baldo turned his head this way and that, looking into our expectant faces. He would not yield to the old man, but dragging him into the street and thrashing him now would seem unsportsmanlike—and just as likely to damage his reputation as backing down. The Don, it seemed, had caught him in a trap, one Baldo was did not have the wits to disarm.

“Fine, then,” he said. “But I’ll have your word. If I show you to be a faker, you’ll take your tricks and leave this place.”

“Agreed,” the Don said, a smile creeping across his face. He then clapped his hands and ordered two pairs of long tables be cleared off and set end-to-end in the center of the room. At his direction, sheets were brought down from the upper chambers and spread over each table.

These modest accommodations in place, the Don explained the terms of the contest. The challenge would begin when both men were so deeply asleep that the sound of an empty pot struck with a ladle could not rouse them. Following the successful performance of this test, the first man to wake, whether minutes later or after many days, would forfeit the contest. The particulars of the trial were left for us to determine, and volunteers presented themselves to stand watch in shifts. The competitors took their places and closed their eyes.

A change came over the Master the moment that he entered into his trance. Like a sea suddenly becalmed, his face became placid, the lines of age smoothing to such a degree that he appeared to regain the freshness of youth.

Oh that smile, blameless and beatific, and yet there was something sphinxlike in it. What unaccustomed pleasures did he relish? What forbidden desires could not be indulged by a man who could master dreams? Or might he choose not to dream at all, preferring instead to abide in the marrow of silence, beyond the reach of any hardship. Blessed with divine forgetfulness and delighting in a death that is not death, who could fail to be happy?

Not long into the second night, it was discovered that Baldo talked in his sleep. He complained about his rations, cursed his captains and his horse, and several times whimpered pitifully for the mother who had died to give him breath. As the night deepened, Baldo’s groaning grew louder and more guttural until finally, just as the cock crowed on the morning of the third day, he sat upright and howled. Crazed and trembling, he leapt from the table.

“Did you see it?” he demanded, gripping the dozing watchman by the shoulders. He’d been visited by an apparition, a perfect likeness of his father down to the thick moustache and the blue-black stains beneath his fingernails. In one of its bloodless hands, the shade had held out a composing stick. With the other, it delved into the pockets of a leather apron, drawing out strips and blocks of lead. It seemed to know the pieces it sought by touch alone, for it kept its gaze fixed on Baldo even as it placed one letter after another into the stick.

Baldo petitioned the ghost to state its purpose and disclose its origin—whether it had fallen from Heaven’s celestial sphere or fled the caverns of the damned through some vent in the earth. But the phantom would not speak. Instead, it held the composing stick before it, presenting a single line of type, now fully set. But unlettered as he was, Baldo could not read the message. A moment later, the shade had turned away and, sliced through by the first ray of dawn, scattered into so many motes of dust.

As for the Don, he continued sleeping peacefully. Looking closely at his countenance, however, some detected a supercilious arch to one eyebrow, a wily curl of the lip that belied the innocence of his smile. Once Baldo had steadied himself, he crouched next to the maestro’s ear, addressing him in a loud voice.

“You’ve had your fun, you old witch. Putting a thing like that into a man’s dreams—won’t you and the devil have a good laugh the next time you meet?” The Don’s chest rose and fell, but he said nothing. “And I’ll grant you’ve got some craft after all, heathenish though it is. If it were up to me, you’d burn for it.” Baldo took the wilted poppy, forgotten until now, out of his pocket. “But you can take your flower now and go back to your own house.” He tossed the blossom onto the Don’s chest, but still the master remained motionless.

Then, as if drawn upward by unseen strings, the Don’s arms floated into the air. Seemingly without his knowing anything about it, his fingers made a series of exquisite gestures. We took their execution as a sign that the Don had entered into some new, elevated stage of meditation. It was clear now that he did not intend to wake until he had favored us with a prolonged demonstration of his art.

Days passed and still the Don reposed in gorgeous sleep. By the middle of the second week, however, the lodgers had grown tired of carrying their boots down the stairs each morning and then lacing them up at the threshold. No longer a solemn, sock-footed procession, they returned to their former habit of tramping down the stairs in a throng, each man scrambling and shoving to be the among the first to the breakfast table. The serving girl, who had once stepped so gingerly around the maestro’s pallet, now bustled by with platters of food, knocking her ample hips against his bier-like bed.

There was a sense, even among those who had been its most ardent spectators, that the show had perhaps gone on a bit too long. An odd compound of feelings stirred within us then, for our admiration of the old man’s art was now adulterated with shame and no small portion of resentment. The infidelity of our attention, our deafness to the subtler registers of the maestro’s instrument—these seemed to each citizen an indictment of his own coarse and uncultivated character.

Yet we took little time to ponder this change of sentiment, for it coincided with the end of the Lenten season, that time of the year in which every muscle and sinew of our communal body labors in preparations for the Holy Week. It is our custom, you see, for the several days that follow Palm Sunday to mount great processions through the town, the execution of which requires the construction of stages and scaffolds, the decoration of wagons, the making of masks and costumes, the adornment of altars, and so on.

The festivities reach their climax on Maundy Thursday, with the re-enactment of the last supper and the carrying of the cross. It is the duty of the prior to choose the surrogate for Christ, usually a man who has petitioned for the part as an act of penance for sins committed earlier in the year. At first light, the prior locks the chosen man in a closet of the sacristy. In the evening, after the holy mass, two of our number, dressed as Romans, bring the man before us. He is barefoot, chained at the wrists, and his face is hidden behind a white hood.

There, before the altar, a crown of thorns is set on his head and he is driven down the aisle by lashes of the whip until he passes under the church’s arch and out onto the piazza. That is when we light our torches and local members of the Brotherhood of the Holy Spirit—hooded, though of course everyone knows who they are—lower a rough cross onto the surrogate’s shoulders. Then the whole town follows the penitent as he drags his burden through the streets. Finally, with bloodied feet, he reaches our imagined Calvary: a grassless hillock just outside the gates that some say resembles a skull.

And we can hardly be blamed, given the pious drama of that spectacle, and followed as it was by the Easter Vigil and the feast celebrating our Lord’s resurrection, for having attended so little to the old man asleep on his table. Neither did we think of him the Monday of the Easter market, that day when we open our gates to artisans and peddlers of all sorts.

In amongst that sundry gathering of minstrels and moneylenders, of chandlers and cheesemongers, there was a young man calling himself Leandro. Attached to a troupe of comic actors, his performance was preceded by a Zanni in a long-nosed leather mask, a cunning servant who sported with a hunch-backed Pantalone. When this pair had finished, the dashing youth capered up the empty crates that served as steps and then stood alone on the makeshift stage.

His face was comely and fresh, with no inkling of a beard. His hair, tawny-gold, was short and curled, the better to display his long forehead and high, delicate eyebrows. The lips of his small mouth were full and when these parted, as in a smile, they disclosed a fetching gap between his front teeth.

Though his manner of dress may have been all the mode amongst the Florentines, it seemed to us fantastic. His doublet, myrtle green, had been slashed almost to tatters—not thoughtlessly, we saw, but by design—so that puffs of lemon chemise protruded through the slits. Where our jackets were loose and reached as far as the knees, the boy’s was short-waisted and fit him closely, not unlike a maiden’s corset. This showed his slender figure to advantage and provided full view of his legs, long and shapely in pleatless hose. To cover his sinful parts he wore a padded pouch, of which modesty prevents me saying any more.

His arms quiet and trunk perfectly erect, Leandro lifted one foot to the level of his knee and with his pointed toes traced perfect circles in the air, all the while keeping to the tambourine’s cheerful measure. This was no country circle dance of the kind all but the lame can perform, but something artful and athletic. His feet moved with complex intentions over the boards, and he pivoted into profile, placing one hand on his hip and gazing coyly over a raised shoulder before leaping straight up, crossing his feet twice at the ankles, and landing in the same stance as before. The end of his performance consisted of a vigorous series of turns—all performed while suspended in the air—and ending with a high kick.

It was the most remarkable display we had ever seen and, compelled by our cries of acclaim, he repeated his dance twice more before we allowed him to leave the stage. That evening we plied him with wine and extracted a promise that he would stay with us for at least a fortnight. He was reluctant at first, for he already had engagements with the actors in other places, but, he supposed, he could use the time to finish work on his book, a treatise on the art of dance that would codify his techniques and secure for him a reputation above even that of Domenico da Piacenza and Guglielmo the Hebrew. At the mention of a book, Baldo—quite drunk and expressing a manly affection for the boy—offered the use of his father’s press (not mentioning, in his enthusiasm, that he knew nothing of its operations).

And that is how Leandro came to pass the spring with us and become our dancing master. In the mornings he practiced his footwork, retiring to his room in the afternoons to read Libro dell’arte del danzare, a copy of the original, transcribed by his own hand. So great was his devotion to his art that in the evenings he offered lessons in courtly dancing to any who showed an interest.

After the evening meal, all of the benches and tables were placed against the walls. The tables bearing Don Albani were moved from their regular place and wedged in the farthest corner. As we prepared the space for the first of these lessons, Leandro asked after our slumbering gentleman. Was the man always thus? He had known of such unfortunates in Venice. It was tragic to see an ancient fellow drink himself insensate night after night; were there no family or friends to look after him, to spare him this last disgrace in his declining years?

Oh no, we assured him, this was no drunkard, but a master of the art of sleep. Leandro seemed not to understand. In his career as a dancing prodigy, he had already served in several courts, yet had never heard of a sleeping master. He admitted, however, that amongst the highborn, trends caught fire and were snuffed out with such celerity that the whole craze for sleeping could have passed before he was born. The boy looked the Don up and down, but then shrugged, appearing to put the matter out of his mind.

On that night and those that followed, Leandro divided us into pairs and showed us a new way of dancing. We learned to greet our partners with a single step forward and back—always with the left foot and taking care not to point the toe or drag the heel. This was followed by a bending of both knees, a sort of bow, but with a straight back and arms at our sides. Although it made us feel foolish at first, we even became willing to mime the kissing of our fingers before commencing each dance.

There were so many steps to learn, to which our young master was always adding new ones. He led us through muffled walking steps and loud, cracking stamps of the heel and toe. There were steps in which we circled one another and others where we sprung to the side or made a little turn; another required the dancer to hop on one foot and swing the other like the clapper of a bell. The youth was very patient with us and though we sometimes stumbled into each other or fell to the ground after a too-ambitious jump, there were no serious injuries and everyone agreed it was a fine time.

Not only did these lessons fill our nights with gaiety, they had other effects as well. Our wives and the young maidens of our town seemed more appealing than before, both more dignified and in better spirits. And there was no man for whom the display of courtly graces did not gentle his condition. Baldo especially was transformed. He drank less and took more care with his appearance and his words. It was as if he had been waiting his whole life for just this kind of instruction—to be shown, down to the smallest gesture, how he ought to behave around other people.

Things went on in this way for several weeks until, one night, as we practiced the greatest yet of Leandro’s miming dances, an elaborately choreographed battle of the sexes, we heard a rasp from the corner where the Don had been installed. His eyes were half-open and he was laboring, with some difficulty it seemed, to sit up. Leandro put a stop to the dance and several us rushed over to attend to the old gentleman.

We helped the Don down from his table and onto a proper bench. In a quiet voice, he bade us bring him a glass of water and a bowl of broth. When these were delivered, he took a sip of each and then asked for the date. He seemed pleased with our answers and nodded, allowing himself a self-satisfied smile at his achievement. It was only then that he inquired about the state of the common room. We had needed to move his table with the others, we explained, in order to make room for the dancing. He looked around, appearing to take everything in and then, looking down into his bowl, set to eating his soup.

There was nothing to do but return to the dance. Leandro hurried us through the middle section of his “Gamomachia”—he had not yet completed the ending—and then, as was his habit on these nights, took up the lute himself and provided us with tunes fit for the slow and stately Padovane rising in crescendo to the quick-stepping Gagliarda. Such a long sleep seemed to have dulled the Don’s senses and left him weak. He watched us with sunken eyes and though we encouraged him to join us, he dismissed the idea with a wave of his hand.

But then, for the last dance, he rose unsteadily to his feet and tottered to the edge of our circle. Out of consideration for the old man, Leandro played a soft, down-tempo number and we each sought out our usual partners. The Don bowed to an imaginary partner, and, watching us out of the corner of one eye, tried out a few steps. His efforts were competent and though he smiled in wan imitation of our joy, gladness seemed not to really touch him.

When the music was finished, while everyone was setting the room for the next day, I took the Don’s folded screen from where we had stowed it behind the bar and brought it to him.

“I think I will go now,” he said. “But it is late and I am weary from my performance. Would you be so kind as to walk with me? It is very dark and I fear I might lose my way.”

I said I would be honored and helped the old man to his feet. Together we proceeded to the town’s smaller, eastern gate, and then onto the darkened path that led to the maestro’s grove of chestnut trees. At the door to his cottage he hesitated.

“All of this,” he said, sweeping his arm in a gesture that seemed to encompass the orchard and the town, the river and the mountains beyond, the sky above us and all the stars. “This splendor. I never knew what to do with it, what it was for.” He stared at my face as if he expected to find an answer written there, but in truth I could not understand him. “Better to go inside and sleep.” He took his screen from me and went inside the house. As I turned to leave, I heard the clatter of a key in the lock.

All this happened years ago, and the grass has grown wild again over the graves of the Albani and the foundation of the cottage has failed and sunk half into the ground. Yet we have not seen the Don since that night and, as far as any of us know, he may sleep there still.